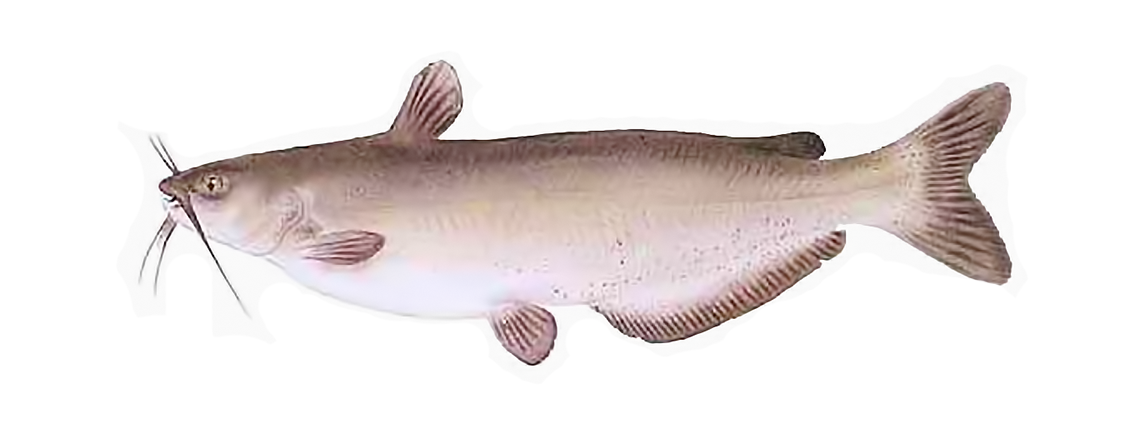

Channel Catfish Habits

Feeding

Catfish have enhanced capabilities of taste perception, hence called the “swimming tongue”, due to the presence of taste buds all over the external body surface and inside the oropharyngeal cavity. Specifically, they have high sensitivity to amino acids, which explains their unique communication methods as follows. The catfish has a facial taste system that is extremely responsive to L-alanine and L-arginine. More specifically, their facial taste system senses heightened levels of L-amino acids in freshwater. Feeding behavior to food is due to amino acids released by food. This is reported to cause maxillary and mandibular barbell movements, which orient the catfish's posture and food search. When the food stimulates the taste receptors, it causes more excitation which see as exaggerated biting, turning, or mastication.

Catfish have enhanced capabilities of taste perception, hence called the “swimming tongue”, due to the presence of taste buds all over the external body surface and inside the oropharyngeal cavity. Specifically, they have high sensitivity to amino acids, which explains their unique communication methods as follows. The catfish has a facial taste system that is extremely responsive to L-alanine and L-arginine. More specifically, their facial taste system senses heightened levels of L-amino acids in freshwater. Feeding behavior to food is due to amino acids released by food. This is reported to cause maxillary and mandibular barbell movements, which orient the catfish's posture and food search. When the food stimulates the taste receptors, it causes more excitation which see as exaggerated biting, turning, or mastication.

Communication

The channel catfish is adapted to limited light conditions. Members of the genus Ictalurus, which inhabit muddy waters, do not depend solely on visual cues. Instead, they are known to rely heavily on chemotaxic cues. Sound production may be another important means of communication among channel catfish and other species living in turbid habitats.

Chemical communication

The North American channel catfish is an ostariophysan, or a bony fish occupying a freshwater habitat. These fishes are known to produce club cells and alarm substances for communication purposes. Both the fish's habitat and the presence of chemosensory cells covering the body are presumably the results of favored selection for this method of communication. Catfishes are capable of producing and recognizing individual specific pheromones. Through these pheromones, a catfish can identify not only the species and sex of a conspecific, but also its age, size, reproductive state, or hierarchical social status. Territoriality in channel catfish is identifiable by a change in body odor, which is recognizable by other members of the same species. This chemical change in the amino-acid composition of the skin mucus can be noted by chromatographic methods, and are not long-lasting; rather, they last only long enough to communicate to other fish in the vicinity. Changes may be the result of the release of the contents of the club cells. These cells do not open directly to the surface of the skin, but injury caused by fighting and other agonistic behaviors may release the cells’ contents. Since catfish have a dominance hierarchy system, information relative to the change of status of any fish is important in recognition of the social strata.

Territoriality in channel catfish is identifiable by a change in body odor, which is recognizable by other members of the same species. This chemical change in the amino-acid composition of the skin mucus can be noted by chromatographic methods, and are not long-lasting; rather, they last only long enough to communicate to other fish in the vicinity. Changes may be the result of the release of the contents of the club cells. These cells do not open directly to the surface of the skin, but injury caused by fighting and other agonistic behaviors may release the cells’ contents. Since catfish have a dominance hierarchy system, information relative to the change of status of any fish is important in recognition of the social strata.

Channel Catfish Species Information

Learn more about this catfish species.

Signal distinction

In the channel catfish, while a communication signal is directed toward the receiver and contains a specific message, an information signal is a part of the general existence of the individual or the group. For example, release of an alarm signal will communicate danger, but the individual's recognition odor is only an information signal identifying one fish from another. With regards to the function and contents of the club cells, the club cells may serve different functions throughout the fish's lifecycle. Variation in the contents of the club cells’ information signals therefore may change with the species’ needs at different stages of life.

Sound production

All species of catfishes can generate sound through stridulation, and many produce sounds through drumming. Stridulation consists of the clicking or grinding of bony parts on the fish's pectoral fins and pectoral girdle, and drumming consists of the contraction of specialized sonic muscles with subsequent reverberation through the swim bladder. Variability in the sound signals created by the channel catfish depends on the mechanism by which the sound is produced, the function of the resultant sound, and physical factors such as sex, age, and temperature. This variation may result in increased complexity of the outgoing signal and may allow for increased usefulness of the signal in interspecies communication. In the channel catfish, sounds are produced only by pectoral stridulation, as this species does not express sonic muscles. However, the swim bladder may still be used to help with audition. Due to the high density of water, sound travels 4.8 times faster and over longer distances under water than in air. Consequently, sound production via stridulation is an excellent means of underwater communication for channel catfish. The pectoral spine of the channel catfish is an enlarged fin ray with a slightly modified base that forms a complex articulation with several bones of the pectoral girdle. Unlike the other pectoral fin rays, the individual fin segments of the spine are hypertrophied and fused, except for at the distal tip. The surface of the spine is often ornamented with a serrated edge and venomous tissues, designed to deter predators. Sounds produced during fin abduction result from the movement of the base of the pectoral spine across the pectoral girdle channel. Each sweep of sound consists of a number of discrete pulses created by the ridges lining the base of the pectoral spine as they pass over the rough surface of the girdle's channel. The stridulation sounds are extremely variable due to the range and flexibility of motion in fin use. Different sounds may be used for different functions in communication, such as in behavior towards predators and in asserting dominance.

Due to the high density of water, sound travels 4.8 times faster and over longer distances under water than in air. Consequently, sound production via stridulation is an excellent means of underwater communication for channel catfish. The pectoral spine of the channel catfish is an enlarged fin ray with a slightly modified base that forms a complex articulation with several bones of the pectoral girdle. Unlike the other pectoral fin rays, the individual fin segments of the spine are hypertrophied and fused, except for at the distal tip. The surface of the spine is often ornamented with a serrated edge and venomous tissues, designed to deter predators. Sounds produced during fin abduction result from the movement of the base of the pectoral spine across the pectoral girdle channel. Each sweep of sound consists of a number of discrete pulses created by the ridges lining the base of the pectoral spine as they pass over the rough surface of the girdle's channel. The stridulation sounds are extremely variable due to the range and flexibility of motion in fin use. Different sounds may be used for different functions in communication, such as in behavior towards predators and in asserting dominance.

In many channel catfish, individuals favor one fin or another for stridulatory sound production (in the same way as humans are right-handed or left-handed).The first ray of the channel catfish pectoral fin is a bilaterally symmetrical spinous structure that is minimally important for movement; however, it can be locked as a defensive adaptation or used as a means for sound production. According to one scholar, most fish tend to produce sound with their right fin, although sound production with the left fin has also been observed.

Hearing

The inferior division of the inner ear, most prominently the utricle, is considered the primary area of hearing in most fishes. The hearing ability of the channel catfish is enhanced by the presence of the swim bladder. It is the main structure that reverberates the echo from other individuals’ sounds, as well as from sonar devices. The volume of the swim bladder changes if fish move vertically, thus is also considered to be the site of pressure sensitivity. The latency of swim bladder adaptation after a change in pressure affects hearing and other possible swim bladder functions, presumably making audition more difficult. Nevertheless, the presence of the swim bladder and a relatively complex auditory apparatus allows the channel catfish to discern different sounds and tell from which directions sounds have come.

Communication to predators

Pectoral stridulation has been considered to be the main means of agonistic communication towards predators in channel catfish. Sudden, relatively loud sounds are used to startle predators in a manner analogous to the well-documented, visual flash display of various lepidopterans. In most catfish, a drumming sound can be produced for this use, and the incidences of the drumming sounds can reach up to 300 or 400 per second. However, the channel catfish must resort instead to stridulation sounds and pectoral spine display for predator avoidance. In addition to communication towards predators, stridulation can be seen as a possible alarm signal to other catfish, in the sense of warning nearby individuals that a predator is near.

Pectoral stridulation has been considered to be the main means of agonistic communication towards predators in channel catfish. Sudden, relatively loud sounds are used to startle predators in a manner analogous to the well-documented, visual flash display of various lepidopterans. In most catfish, a drumming sound can be produced for this use, and the incidences of the drumming sounds can reach up to 300 or 400 per second. However, the channel catfish must resort instead to stridulation sounds and pectoral spine display for predator avoidance. In addition to communication towards predators, stridulation can be seen as a possible alarm signal to other catfish, in the sense of warning nearby individuals that a predator is near.

Similar species

- The Blue Catfish, I. furcatus, occurs over much of the range of the Channel Catfish but lacks dark spots on the body, and has a straight-edged anal fin with 30-35 rays and a straight predorsal profile.

- The Headwater Catfish, I. lupus, is nearly identical to the Channel Catfish but has a deeper caudal peduncle, and a broader head and mouth.

- The Yaqui Catfish, I. pricei, has a shorter pectoral spine, dorsal spine, and anal fin base.